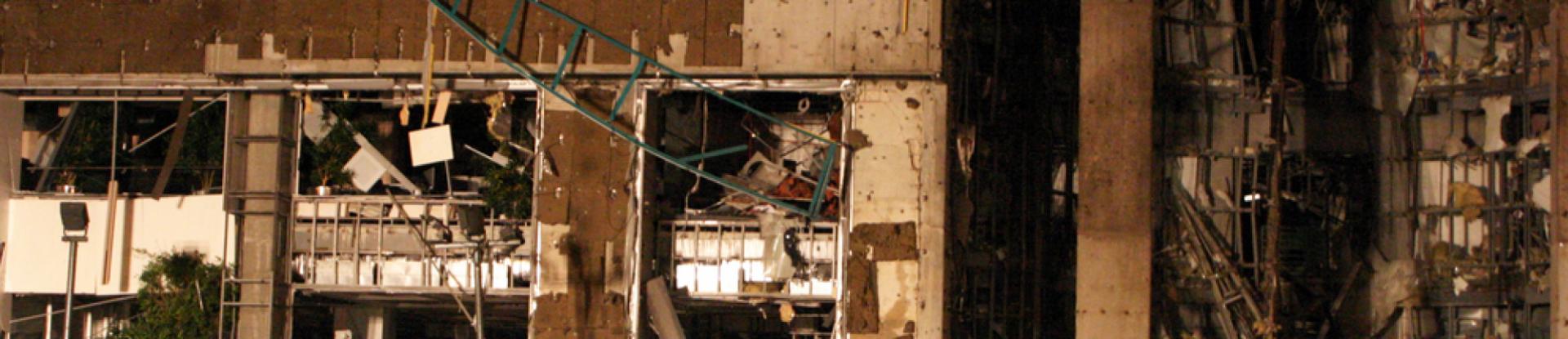

The devastating explosion in the port area of Beirut on 4 August has captured the world’s attention and sympathy for the people affected.

However, such large explosions are not uncommon. A series of explosions almost five years ago (12 August 2015) at a container storage depot at the port of Tianjin in China killed 173 people, according to official reports, and injured hundreds of others. A second, larger explosion at the site involved the detonation of about 800 tonnes of ammonium nitrate. This should be compared to the 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate that reportedly detonated in Beirut this week. The numbers of killed and injured in Beirut have still to be declared.

The UK has also experienced large explosions which, while devastating, have thankfully not been so injurious. On the night of 10 December 2005, a petrol tank at the Buncefield oil storage depot was filling with petrol but a gauge stuck resulting in large quantities of petrol overflowing and a vapour cloud igniting that caused a massive explosion and a fire which lasted five days. There were 43 reported injuries but no fatalities.

The resulting inquiry on the Buncefield incident concluded that:

- ‘There should be a clear understanding of major accident risks and the safety critical equipment and systems designed to control them. This understanding should exist within organisations from the senior management down to the shop floor, and it needs to exist between all organisations involved in supplying, installing, maintaining and operating these controls.

- There should be systems and a culture in place to detect signals of failure in safety critical equipment and to respond to them quickly and effectively. In this case, there were clear signs that the equipment was not fit for purpose but no one questioned why, or what should be done about it other than ensure a series of temporary fixes.

- Time and resources for process safety should be made available. The pressures on staff and managers should be understood and managed so that they have the capacity to apply procedures and systems essential for safe operation.

Once all the above are in place:

- There should be effective auditing systems in place which test the quality of management systems and ensure that these systems are actually being used on the ground and are effective.

- At the core of managing a major hazard business should be clear and positive process safety leadership with board-level involvement and competence to ensure that major hazard risks are being properly managed.’

Buncefield is clearly not Beirut. However, the same lessons may emerge albeit in a different setting and with a different cause. It is tragic that lessons have to be re-learnt.

For further reading, please visit our Knowledge Hub.