By Massimo Pani MSc CPP AMBCI

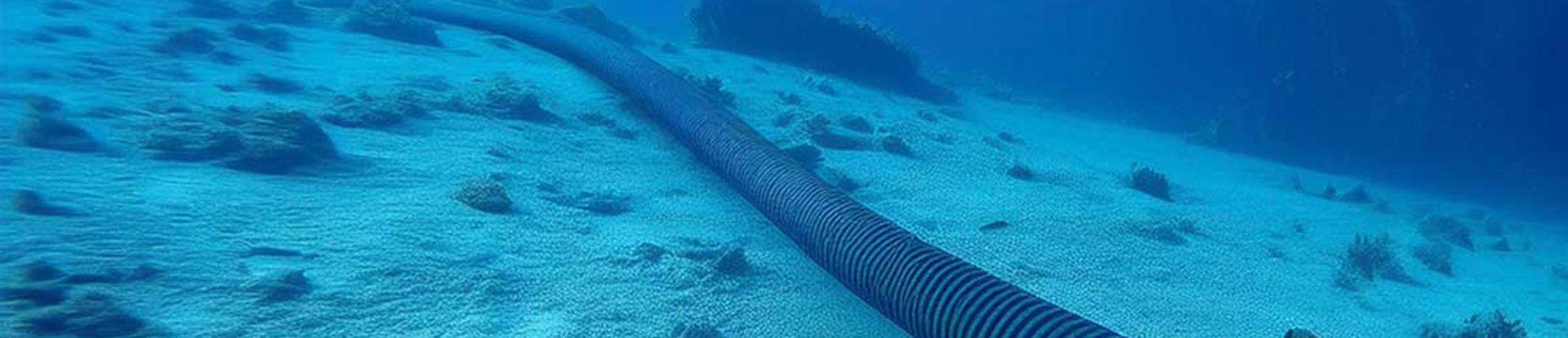

In an age where digital connectivity underpins every aspect of our lives, recent disruptive events have cast a spotlight on one of our most critical yet vulnerable arteries: undersea fiber optic cables and infrastructure. At the end of 2024, the ocean’s seabeds had approximately 559 active submarine cables, for an extension of 1.4 million kilometers and a market value of $29.94 billion. This number is growing every year as big tech companies lay and operate their own cables, Amazon, Google, Meta and Microsoft alone now control around half of all undersea bandwidth worldwide.

The submarine networks represent the backbone of intercontinental internet connectivity, as they facilitate nearly 95% of global data transmission. Often described as the “world’s information super-highways”, they provide high bandwidth connections needed for a vital range of activities of our modern society: from financial transactions to cloud computing services to military secret communications and daily internet usage. The scale of our dependence on this infrastructure is staggering, it is estimated that in the financial sector alone these cables carry $10 trillion worth of financial transactions every day.

Assessing the Nature of the Threat in the Deep

The vital importance of the global undersea cable network is matched only by its fragility. According to the International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC), it is estimated that between 100 to 200 undersea cables are damaged every year. It is a multifaceted threat landscape: accidental cuts (e.g., from anchors or shark bites), damage caused by natural disasters (earthquakes, landslides or tsunamis), as well as sabotage (hostile intelligence tampering and severance). Beyond accidental damage from shipping and fishing activities, there’s growing concern about deliberate sabotage and physical interference. A recent string of incidents in the waters of Taiwan, the Red Sea, Estonia, Finland, Norway, Sweden, France, and Germany[1] has raised awareness in the international community about how vulnerable these cables can be to physical attacks, whether through direct cutting or the use of specialized equipment to degrade signal quality. In addition, there is the surveillance risk posed by advanced technological capabilities which may allow hostile actors to tap into these cables[2], potentially intercepting sensitive data without obvious physical damage. This presents an even more subtle but equally serious threat to global communications security. Finally, there are constant geopolitical vulnerabilities: the concentration of cables in certain geographical chokepoints creates strategic vulnerabilities that could be exploited during international conflicts or tensions.

Since 2022, there has been an ongoing US-Europe re-evaluation of the risks emanating from China and Russia to underwater infrastructures, with working groups discussing the development of alternate cable routes connecting Asia, Europe, and North America, as well as enhancing resilience and supplier diversification. In 2023, NATO established several initiatives, including a Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure in the United Kingdom, and the endorsement of a new Digital Ocean Vision, an initiative aimed at enhancing maritime situational awareness and surveillance “from seabed to space”. More recently, on January 15, 2025, a NATO mission dubbed “Baltic Sentry” was unveiled to enhance the security of undersea infrastructure in the Baltic Sea. This robust military enforcement, which will include a range of surveillance assets and technologies, and among them, for the first time, a small fleet of naval drones, represents an important paradigm shift in the protection of critical undersea infrastructure. Indeed, the current provisions under international law[3] aimed at protecting subsea cables are not suited for an era of hybrid aggression. Expanding jurisdictional authority to address intentional cable damage on the high seas or in territorial waters remains unlikely, and no meaningful international treaty negotiations have been initiated to address this issue.

The Impact of Undersea Cable Disruptions on Business Continuity and Global Supply Chains

Unlike Russia, whose internet cables mostly run overland, the communication lines of Western and other global partners are deep undersea, and this asymmetrical vulnerability could be easily exploited by threat actors. Therefore, businesses (financial services, e-commerce platforms, and technology firms) and global supply chains that are heavily reliant on real-time communication transmitted by undersea cables could experience severe consequences if sabotage becomes a recurring tactic adopted by adversarial nations. According to Forbes, the average cost of downtime has inched as high as $9,000 per minute for large organizations, while for critical-infrastructure enterprises, particularly in finance and healthcare, downtime represents a multidimensional economic catastrophe: the $5 million hourly cost encompasses far more than immediate productivity losses—it’s a comprehensive destruction vector targeting regulatory compliance, market valuation, client trust, and long-term competitive positioning. Another recent study highlighted the frightening consequences of three undersea cable cuts in the Red Sea in 2023 estimating the costs of disruptions for businesses to be $3.5 billion.

Recent cable severances in the Baltics did not result in an internet blackout, but just in a lower bandwidth and disruption for individual users and companies, as data traffic is typically rerouted very quickly in areas served by multiple subsea cables. However, cable damage, especially if severed in a row, has the potential to leave an entire nation cut off from global data, leaving them solely reliant on satellites to communicate. Therefore, businesses can suffer significant disruptions in terms of loss of communication, financial breakdowns and reputational damage. The inability to carry out many financial transactions and commercial communications could trigger panic in the capital market, increase market uncertainty, and possibly initiate a financial crisis.

Practical Strategies to Diversify and Protect Communications Infrastructure

The following recommendations suggest a series of steps businesses can take to counter the risk of a blackout, diversifying their communication infrastructure while ensuring continuity in the face of potential disruptions.

Firstly, it is recommended to map current communication dependencies and identify critical communication needs, testing the failover system. In sequence, it is advised to evaluate the risks associated with undersea cable disruptions, geopolitical threats and natural disasters. By doing so, companies should develop targeted mitigation strategies. These assessments should then be conducted periodically to adapt to evolving threat landscapes.

As an immediate action businesses could contract with a number of providers. Indeed, multi-carrier networking involves using multiple internet service providers (ISPs) to ensure redundancy and load balancing. By establishing connections with various carriers, businesses can reduce the risk of complete outages due to a single provider’s network failure. This strategy enhances resilience and improves overall network performance.

In the medium term, it is recommended to adopt one or more of the following practical implementation steps:

- Establish terrestrial cable systems as an alternative to undersea communication routes. While undersea cables are vital for intercontinental communication, terrestrial cable systems can serve as complementary infrastructure. Businesses can invest in or partner with providers of land-based fiber optic networks, which offer high-speed and reliable connections. These systems can act as backups and reduce dependency on undersea cables.

- Develop regional mesh networks, connecting multiple office locations together, each with its own internet. Wireless mesh networks consist of interconnected nodes that facilitate data transmission without relying on a central infrastructure. These networks are highly resilient and can operate independently in the event of a major disruption. Businesses can deploy wireless mesh networks within their facilities or across different structures to ensure continuous local communication. This solution is very reliable in case one location loses internet, as communications can pass through another location’s connection. It may be a helpful solution for businesses that have multiple locations in the same region.

- Install a satellite backup system. This is a cost-effective solution completely independent from ground-based problems and works almost anywhere. It is particularly recommended for businesses that work in remote locations, or those prone to natural disasters or geopolitical conflicts.

- Leverage cloud-based services. This offers businesses scalable and redundant data storage and processing capabilities. By utilizing multiple cloud service providers across different geographic regions, companies can ensure data redundancy and minimize the impact of localized disruptions. Cloud-based solutions also enable flexible access to critical applications and services.

Coordinated Public-Private Initiatives

By 2030, experts predict an increase to 650 subsea cables, driven by the rising global demand for digital connectivity and new investments in underserved regions (particularly Africa and Asia) with an estimated value of $49.31 billion by 2033. Such a cable magnitude may lead to “choke points” that will increase the risk of sabotage, accident, or a natural disaster, affecting simultaneously multiple telecommunication providers, and potentially disrupting, or degrading communications for many users, including governments, individuals, and economies. Therefore, even if criticalities persist, it is pivotal that the following additional initiatives are fostered with a coordinated, multi-stakeholder approach:

- Map vulnerabilities. Despite the recent initiatives aimed at increasing resilience and ensuring the protection of undersea cables, the level of understanding and preparedness still varies greatly from country to country. It is crucial to gather a better global picture of undersea cables, share best practices and update international maps of undersea cable routes with transparent and accessible data for operators, governments, and regulators to reduce accidental damage.

- Promote resilience of materials, supply chain, and vessels. Businesses and policymakers should advocate for telecommunications companies to invest in better and more resistant components of subsea cables, (steel, copper, silicon, and fiber optic components), while developing sufficient diversity, and alternatives to the supply chain providers, if components are not suitable or available. Redundancy and backup systems of undersea cables should be prioritized to sustain damage, sabotage or accidents, allowing traffic to be rerouted. The resilience and security of sea cables should be ensured with greater availability of specialized vessels in all geographically dispersed areas of the world, including the Arctic.

- Invest in the development of new protective technology. Public-private partnerships should be incentivized to develop innovative technologies needed to secure and protect current and future subsea cables. To this end, the EU and NATO must invest in the exchange of know-how and technologies between allied governments and between public and private actors and earn the trust of all relevant stakeholders to pursue collective solutions. It would also be advisable to create global benchmarks for cable installation, redundancy, and cybersecurity measures, ensuring infrastructure can withstand natural disasters, intelligence tampering and sabotage. Encourage the adoption of technologies like real-time monitoring systems, automated repair undersea drones, and AI-driven network traffic analysis to quickly detect and respond to threats.

- Stand joint naval patrolling missions. In line with the “Baltic Sentry,” similar regional initiatives within NATO should be created to boost deterrence against threats to undersea infrastructure in the North Sea, the Mediterranean, and the North Atlantic.

- Modernize the international legal instruments and governance of undersea cable provisions. The primary legal framework governing undersea cables is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). While UNCLOS, which was stipulated in 1982 and adopted in 1994, provides foundational principles to regulate all ocean space, its uses, and resources, it requires modernization to address contemporary issues. Indeed, it should include explicit provisions addressing modern risks such as cyberattacks, sabotage, and broaden definitions of “intentional damage” to reflect current asymmetric threats to cable infrastructure. It would also be advisable to Standardize Rules for Military Activity, defining clear international norms for military activity near critical cable systems to prevent accidental damage or exploitation for espionage.

- Introduce liability mechanisms. Establish liability frameworks for accidental or malicious cable damage, ensuring affected parties receive compensation.

- Develop a global undersea cable governance body: Establish a UN-backed organization dedicated to coordinating cable security, repair, and dispute resolution, like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) or International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

Conclusions

Undersea cables are the backbone of modern connectivity, enabling a globally interdependent digital economy. However, their importance is matched by their vulnerability to both accidental and deliberate threats. Disruptions can jeopardize business continuity, destabilize supply chains, and pose significant economic and security risks.

Addressing these vulnerabilities demands a multi-faceted approach. Businesses must diversify their communications infrastructure through redundant systems, multi-cloud strategies, and satellite solutions. Collaboration between the private sector, governments, and international organizations is vital to strengthen legal frameworks, improve intelligence sharing, and modernize protective measures. By adopting innovative technologies such as real-time monitoring and automated repairs, stakeholders can safeguard critical infrastructure against emerging threats.

Ultimately, a coordinated global effort to modernize legal instruments, implement best practices, and enhance resilience will ensure the continued reliability of undersea cables, securing the foundation of the world’s digital connectivity and economic stability.

About the Author:

Massimo Pani MSc CPP AMBCI is a Geopolitical Risk & Security Expert of the Italian Carabinieri Corps, with over 30 years of experience in global security, intelligence, counterterrorism, and crisis management. He has a distinguished background in high-stakes environments, including deployments with NATO and the EU in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Afghanistan. With expertise in optimizing business delivery and implementing innovative solutions to complex challenges, Massimo has advised on security and crisis management at the highest levels. Drawing from a robust career in international police cooperation and strategic advisory roles, Massimo provides insightful analysis and practical guidance on proactive crisis prevention for leaders.

He may be contacted at: Massimo.pani@hotmail.com

[1] On 26 September 2022, the Nord Stream pipeline explosions, which damaged submarine infrastructure; in October 2022 coordinated and unprecedented attacks disrupted internet services in France and Globally; on January 7, 2022, an undersea fiber optic cable connecting the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard to the mainland was severed; in March 2023 Taiwan Strait Submarine communication cables disrupted; in October 2023, undersea cables running between Estonia, Finland and Sweden were damaged, along with the Balticconnector gas pipeline; on 7-8th February 2024 multiple underwater cables between Europe and North America were severed, causing significant communication disruptions; on 24 February 2024 three undersea cables were damaged in the Red Sea causing a significant impact on communication networks in the Middle East; In November 2024, two cables in the Baltic Sea were severed. The first cable, C-Lion1, connects data centers in Finland and Germany; the second cable connects Sweden and Lithuania. On 26 January 2025, a fiber optic cable was damaged between Sweden and Latvia.

[2] In 2018, the Japanese government reportedly discovered a Chinese wiretapping device on a cable near Okinawa.

[3] The 1884 Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).